Damaged dolphin noses + new Angolan gecko + victory for seabirds + dormice diary

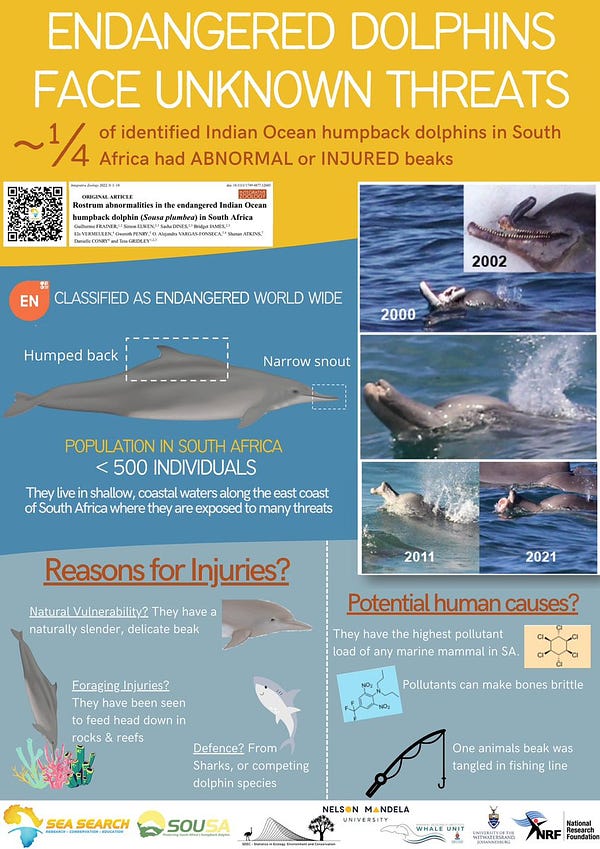

Why are endangered dolphins in South Africa breaking their noses?

Endangered Indian Ocean humpback dolphins in South Africa are showing up with damaged beaks, or rostrums, scientists say.

It could point to the effects of pollution.

There are only around 500 of these dolphins living in South African waters. Surveys carried out from 1998-2021 found 31 dolphins with varying levels of damage to their beaks, or rostrums.

The study published in Integrative Zoology says that humpback dolphins in the waters off KwaZulu-Natal province have been recorded with the highest levels of organochlorines of any marine mammal in South Africa; DDT concentrations in the species are among the highest levels reported in dolphins globally.

“Injuries on the rostrum could be exacerbated due to low bone density caused by contaminants thus resulting in the severe conditions observed,” the authors note.

They do, however, suggest other possible reasons, including clashes with more prolific bottlenose dolphins and the humpback dolphins’ method of fishing in coral reefs, which involves probing crevices with their long beaks.

If they come across a rock-dwelling fish, they snap it up with a sideways jerk of the head. This could result in injuries from “collision with sharp reefs or potentially getting their rostrums stuck in crevices,” the study says.

Why a striking new Angolan gecko species has got scientists excited

Scientists in Angola have discovered a new species of gecko in the southern coastal province of Benguela. The gecko belongs to the genus Kolekanos, and here’s why that’s exciting. Until now, it was thought that there was only one species in this genus: the slender feather-tailed gecko, or Kolekanos plumicaudus. The latter is distinctive because it has elongated scales on its tail that resemble feathers, hence the name.

But Angolan researcher Pedro Vaz Pinto was camping in Carivo, southern Benguela Province, in August last year when he discovered what was evidently a gecko from the same genus. This one, however, had spiny scales on its tail, not feathery ones. Pinto told his colleagues about the discovery, and they returned to the area a few months later to collect some specimens. They have described them as a brand new species in the journal ZooKeys.

The discovery, Pinto’s colleague Javier Lobon-Rovira writes in a blog post, “highlights how poorly explored and understood some regions of Angola remain.”

You can see some photos of this beautiful gecko in his blog post.

Fun fact: kolekanos = Greek word for long, thin person, a reference to the flattened, slender bodies of these animals.

Phenomenal breeding success on remote seabird colony after purge of invasive mice

In the South Atlantic, halfway between Cape Town and Buenos Aires, is a tiny island that conservationists say hosts as many seabirds as the UK.

It’s called Gough Island.

Nearly all the Tristan albatrosses in the world breed on Gough. This critically-endangered species is known to forage off the coast of southern Africa. Its chicks, and those of other seabirds nesting on Gough, have faced terrible predation from mice that were introduced on the island by seal hunters more than a century ago.

A massive project to eradicate the mice by dropping poisoned bait across the island failed last year. Survivor mice were spotted soon afterwards.

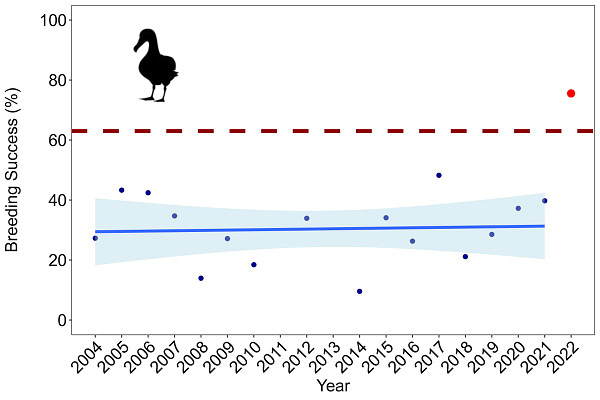

It will take time for mouse numbers to once more threaten the chicks of ground-nesting seabirds. In the meantime, conservationists on Gough are reporting the best breeding success for the Tristan albatross in more than 20 years: 76% this year, up from an average of 32%.

Other species have registered similar gains, including the critically-endangered MacGillivray’s Prion, which have increased their breeding success from an average of 6% with mice, to 82% this year.

“This year has shown us what seabirds can achieve when their chicks are not eaten by mice – and this gives us a determination to return to Gough in the future and remove the mice forever,” reads a statement from the restoration team.

Dormice Diaries

Speaking of mice, but this time not invasive ones, the two orphaned dormice we rescued when only four days old around a month ago are doing well.

I marvel at their speed. They scoot up and down forearms, down shirt sleeves, through armpits, out of the backs of collars, down torsos, and into pockets.

Our daughter recently bought a book on mouse-keeping to help her care for these two orphans. Dude and Andrew, as they’re known, live in a place she calls ‘Mousetopia’. It’s a black plastic crate with plenty of air and space and a secure lid.

The mice are served regular meals according to a menu she’s drawn up. Chopped blueberries, crushed nuts and ProNutro cereal served in milk bottle tops.

Amenities include an empty tea bag box filled with wool, a wooden walkway spanning the length of the crate, a ladder, and a maze made from cardboard toilet roll holders slotted together at various angles.