Ex-poachers do good | Nigerian honey seekers | Invasive flame trees | Extraordinary insects

Zambian ex-poachers help to promote native fruit trees

Ex-poachers in Zambia are helping to promote agroforestry and boost food security thanks to their “vast knowledge” of indigenous fruit trees.

The former poachers will assist in collecting seeds of the trees for a project aiming to help 5,000 rural families.

The plan is to help each of these 5,000 households to plant “a portfolio” of indigenous fruit trees, at least one of which will produce food for the family to harvest each month of the year.

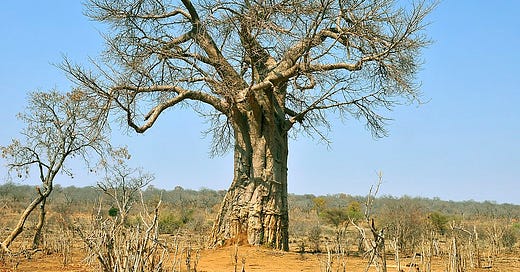

The local species include the baobab, the corky monkey-orange, and the Batoka plum.

Indigenous fruit are highly-nutritious but seriously underrated, say those behind the project, which is being spearheaded by the Center for International Forestry Research–World Agroforestry Centre (CIFOR-ICRAF).

The lack of quality seeds to grow these trees is, however, a problem.

“At present, there is simply no seed for many of the species that communities have identified [for producing useful food crops] — let alone quality seed collected from excellent mother trees,” said Stepha McMullin, the project leader.

This is where the ex-poachers come in.

Twenty-four former poachers, some of whom have served time in prison for killing wildlife, are among those who have undergone training to be part of the project.

They are reported to have acquired “a vast knowledge in indigenous fruit” during their time as poachers in some of Zambia’s wilderness areas.

Now, with their poaching days behind them, seed collection will provide them with a way “to improve their livelihood while preserving these trees,” said Rosa Katanga, a specialist with the Community Markets for Conservation (COMACO) group, which is part of the project.

A baobab tree | Luis Bartolomé Marcos | Wikimedia

Nigerian communities enlist the support of honey-seeking birds

Scientists have discovered that a number of communities in rural Nigeria still enlist the help of the greater honeyguide bird to help them find wild bees’ nests.

The human-honeyguide interaction used to be a lot more common in Africa, but is dying out in many regions.

The discovery that it is still alive and well in parts of Nigeria will be welcome news for those who see this partnership as a rare case of human-wildlife coexistence on a continent often in the news because of human-wildlife conflict.

Greater honeyguides attract the attention of humans willing to cooperate and lead them to wild bees’ nests.

The human partner then opens up the nest to collect the honey and leaves a reward of honey, wax and larvae for the bird.

Nigerian ornithologist Afan Anap Ishaku writes in a recent blog that the practice is especially active among the Fulani and Mambila communities.

She interviewed a total of 58 people from eight villages of mixed cultural backgrounds.

All of them acknowledged using the greater honeyguide — known to the Fulani as Gundaru; the Hausa as Tsuntsun Zuma, the Afizere as Akpereng, and the Mambila as Nyinyip — to track down wild bees’ nests.

But, as in other parts of Africa, the partnership is under threat, noted Ishaku.

“Some 77% of people thought that in particular, the role of honeyguides in honey-hunting has changed over time, which they associated with declining honeyguide populations, environmental factors and habitat degradation,” she wrote.

A greater honeyguide | Wilferd Duckitt | Wikimedia

African tulip tree seeds float ‘over 1,000 kilometres’ on the wind

At this time of the year the streets of Harare, in Zimbabwe, are ablaze with the glowing orange flowers of the African flame tree, also known as the fountain tree, or the African tulip tree.

The tree has a wide distribution extending all the way from Ghana, in West Africa, to Tanzania, in East Africa.

It is not indigenous to Zimbabwe, but was evidently popular as a street tree with municipal officials, who overlooked one major flaw: the trees are deciduous and typically lose all their leaves during the height of Zimbabwe’s dry season.

The trees’ bare branches offer little or no shade in baking October heat, just when it’s needed most.

They evidently weren’t the only ones beguiled by the striking flowers into overlooking some of the tree’s drawbacks.

The delicate seeds, encased in light film, are easily spread by the wind. That’s a big problem, not in Zimbabwe, but in places where cultivated trees have now become invasive. One of those places is the Island of Tahiti, in the South Pacific.

Using atmospheric trajectory models, a group of French scientists has discovered that seeds from African tulip trees growing on Tahiti could spread via long distance seed dispersal to its neighbours in the Society Islands, an archipelago that is part of French Polynesia.

“Wind-dispersed seeds originating from trees on the island of Tahiti could reach most of the Society Islands and disperse as far as 1,364 km (847 miles),” the researchers wrote in their study published in the journal Ecological Applications.

African flame tree in Harare’s National Botanic Garden | Ryan Truscott

Nature Notes: Extraordinary insects

A globe skimmer — a migratory dragonfly to Africa from Asia — made an emergency landing in our hedge in Harare after one stormy night. She sat motionless as the sun dried the moisture on her wings.

It gave me the chance to photograph her and to consider what Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson says in her book, Extraordinary Insects. The Norwegian scientist states that while lions catch prey in one out of every four attempts, and great white sharks fail in half of all hunting attempts, dragonflies have a 95% success rate.

Their eyes give them a massive advantage. Each eye contains around 30,000 small eyes, allowing it to see and process up to 300 images per second. But, as she explains, their skill as hunters also comes down to their command of the skies.

"Their four wings can move independently of one another, which is unusual in the insect world,” she writes.

“Each wing is powered by several sets of muscles, which adjust frequency and direction. This enables a dragonfly to fly both backwards and upside down, and to switch from hovering motionless in the air to speeding off at a maximum speed of close to 50 kilometers [31 miles] an hour."

A globe skimmer dries its wings in Harare | Ryan Truscott