Rare Pangolin Rediscovered in Senegal After 24 Years

A camera trap survey designed to find West African lions in Senegal has also detected the presence of giant pangolins for the first time in nearly a quarter of a century.

A total of 217 cameras were set up at 111 sites throughout Niokolo Koba National Park (NKNP) last year, between February and May. In addition to lions, the cameras captured evidence of 45 different mammals, including one image of a lone giant pangolin in a dry river bed in the east of the park.

It’s Senegal’s first official record of a giant pangolin – the largest of Africa’s four species of scaly anteaters – since 1999. And where there is one there are likely to be more. Pangolins are extremely shy, nocturnal creatures that are notoriously hard to document.

Five previous camera trap surveys in the same park from 2019-2022 captured no sign of them.

Giant pangolins are thought to be present in just 5% of West Africa’s national parks, so it’s welcome news to know that they’re still alive in Senegal.

The job of protecting them in NKNP, however, is more pressing than ever.

The only other place the species was recorded in the past was in the Basse Casamance National park, in the south of the country. But members of the Movement of Democratic Forces of Casamance, a separatist group, are reportedly present there, making the future of that park’s pangolin population uncertain.

Senegal’s Niokolo Koba National Park | Niels Broekzitter | Wikimedia Commons

African Army Ants Amputate Toes of Migrating Nightjars

Scientists conducting a long-term study on red-necked nightjars that migrate thousands of kilometers to Spain each summer from West Africa have found that some of the birds have mutilated toes or feet: and the perpetrators of these injuries are African army ants.

Although the percentage of birds found with missing toes was less than 1% of the total number captured, this could be an underestimate. Only birds that survive their injuries might be the ones making it back to their European breeding grounds in early May, the study says.

Others could be dying from complications like sepsis or opportunistic infections triggered by the ant bites. The loss of toes could also hinder the birds’ ability to groom their feathers and rid themselves of parasites.

The researchers say most nightjars in their study area in Doñana National Park, southern Spain, migrate to Mali and Guinea in West Africa during the northern hemisphere’s winter. These two countries possess at least 20 different species of army ants, which belong to the genus known as Dorylus.

Nightjars are especially vulnerable to their bites because army ants forage on the ground where the nightjars roost or perch while hunting for flying insects like moths.

Some of the birds captured by the researchers in Spain still had ant mandibles embedded in their feet after their long flight back from Africa, according to the researchers.

One adult female “missed three toes of the right foot and one lateral toe and the claw of the medial toe on the left foot.”

A red-necked nightjar in Portugal | Olivença | Wikimedia Commons

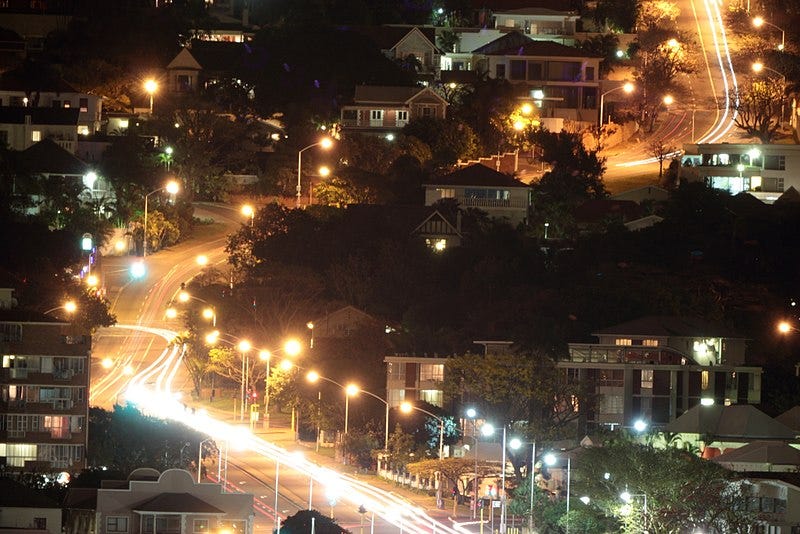

Power Cuts in SA Present Chance to Study Animal Behaviour: Scientists

A group of scientists suggests that scheduled and frequent power outages across South Africa provide the world with its first opportunity to study the impact of artificial light on animal behaviour.

The scientists, led by Arjun Amar from the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, say that the impact of Artificial Light at Night – known by its acronym ALAN – and its regular absence during scheduled power outages (known locally as load-shedding) could be examined across a wide range of habitats and species.

These range from Cape Town, with its Mediterranean climate in the south, to the port city of Durban, with its tropical climate in the east.

“The size of load-shedding zones typically encompasses the home range of most species, ensuring that for some individuals their entire habitat goes dark during times of load-shedding,” the researchers state.

Load-shedding has increased in intensity in South Africa from just 75 days in 2021, to 335 days in 2023, they report. So, despite the inconvenience this presents to people, animal research opportunities abound.

Urban areas with high crime rates could be dangerous to survey in darkness, the researchers note, but this could be overcome through the use of remote-sensing technologies, such as GPS tracking devices, camera traps and remote acoustic monitors.

Night lights in Durban, South Africa | landagent | Wikimedia Commons

Nature Notes: Feathery Forensics

A small drama unfolded in our garden over the weekend.

I found a pile of feathers beneath the Lady Chancellor tree, then noticed one tiny feather float down from the branches above. Looking up I saw the carcass of a bird lying on a thick, horizontal branch.

I climbed up to get a better look and discovered the remains of what might have been a young turaco, or maybe a grey go-away-bird. There was fluffy down still on the body, and some of the plucked feathers lying on the ground were pin feathers: not yet fully formed and still partially encased in keratin. Most of the carcass lying on the branch was still intact; only the head was missing.

I wondered if the killer had stashed its prey and would return, leopard-like, to finish it off.

Later, while out in the garden, I heard an alarm call from a dark-capped bulbul and guessed the hunter had returned. I crept towards the Lady Chancellor but before I could catch sight of it on its perch, an African goshawk took flight, dipping beneath the low branches of a cassia tree, then gliding over the wall and into the neighbour’s garden.

The carcass, I noticed, had now been picked almost bare and when I went back the next morning, it was gone.