Munching ‘Winged Sardines’ | Elephant Tree Threat | Rethinking ‘Hippy Apes’ | Black Cuckoo

Hyenas Snack on ‘Winged Sardines’

Scientists have for the first time recorded spotted hyenas snatching small quelea birds out of the air and off the ground as their vast flocks congregated beside a watering hole in Namibia’s Etosha National Park.

Spotted hyenas are apex predators capable of killing zebras and large antelopes, robbing other carnivores of their prey, or scavenging on carcasses.

And although they’re known to occasionally kill bigger birds, like ostriches and flamingos, there have been very few reports of them feeding on small birds.

Red-billed queleas are grain-eaters considered a pest by wheat farmers because they can devastate crops.

They are so abundant they’re sometimes referred to as “feathered locusts”, but they could also be likened to “winged sardines”.

Like the large schools of sardines that migrate along the coast of South Africa attracting whales, dolphins and seabirds in their wake, so the quelea flocks in Namibia attracted both mammalian (hyenas and black-backed jackals) and bird predators (tawny eagles, a marabou stork and lanner falcons).

A video clip captured by the researchers shows one hyena loping among swarming queleas, catching one and swallowing it whole.

The team calculates that the hyenas’ average capture rate was one quelea every three minutes. It is not, however, known whether quelea hunting is something unique to the Etosha hyenas.

“Since the observations were limited to a single waterhole, it is possible that the described foraging was specific to the hyenas from the observed clan and occurred as an opportunistic response to [an] abundant food source,” the researchers state.

Spotted hyena hunting quelea birds at a waterhole in Namibia | Miha Krofel

Elephant Tree ‘Hedging’ Threatens Birds, Squirrels, Skinks

A study in Zimbabwe’s Gonarezhou National Park shines a light on a problem facing national parks across the region – the coppicing of dominant hardwoods known as Mopane trees – by hungry, confined elephants.

It appears that this coppicing or “hedging” of Mopane trees – in which big trees are snapped or pushed over by elephants – is also recorded in some parks in Botswana, South Africa and Zambia.

The hedging negatively impacts other animals that nest or live in Mopane tree cavities: birds like hornbills, chats and barbets, reptiles like lizards, skinks and snakes and mammals like tree squirrels.

The squirrels face a double whammy: the loss of breeding holes and Mopane seeds, a food source for them that is greatly reduced by hedging. This, the authors of the study state, “is expected to impact on their numbers and on the numbers of the many predators which prey upon them.”

A solution to reducing elephant density lies in a regional initiative known as Transfrontier Conservation Areas (TFCAs).

Gonarezhou belongs to the Greater Limpopo TFCA. During times of food scarcity some of Gonarezhou’s 10,000-or-so elephants can, in theory, cross from south-eastern Zimbabwe to neighbouring Mozambique where there is adequate grazing in that country’s Banhine and Zinave National Parks (elephant bulls who do most of the damage to Mopane trees would much prefer to graze on soft grass than browse on tree bark).

The problem, as the authors state, is that Gonarezhou’s elephants are reluctant to cross into Mozambique due to unchecked hunting along the border, and increased human settlements now blocking their way.

Gonarezhou National Park | Ralf Ellerich | Wikimedia Commons

Africa’s ‘hippy apes’ aren’t as peace-loving as previously thought

Bonobos have the reputation for being the most peaceful of all the great apes.

It has led to them being nicknamed the “hippies” of the ape world, due to their propensity to “make love not war”.

A new study does not necessarily overturn that idea, but it does provide a more nuanced view of bonobos, which are only found in the forests of western and central Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

A team of scientists analysed thousands of hours of data gathered from following bonobos in the DRC’s Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve, and compared that information to thousands of hours of similar observations of chimpanzees in Tanzania’s Gombe National Park.

They discovered nearly three times’ more aggressive encounters between male bonobos than among closely-related chimpanzees, though bonobo aggression was never fatal.

Aggressive male bonobos were also found to be more successful at mating, suggesting there is a genetic advantage to be obtained through this behaviour. Until now, primatologists believed that bonobos adopted non-aggressive behaviour to survive and pass on their genes.

“Our findings of higher rates of male-male aggression in bonobos indicate that aggression remains an important part of the behavioural repertoire,” the team behind the study says.

Bonobos in the Kokolopori Bonobo Reserve, DRC | Maud Mouginot

Nature Notes: The Black Cuckoo

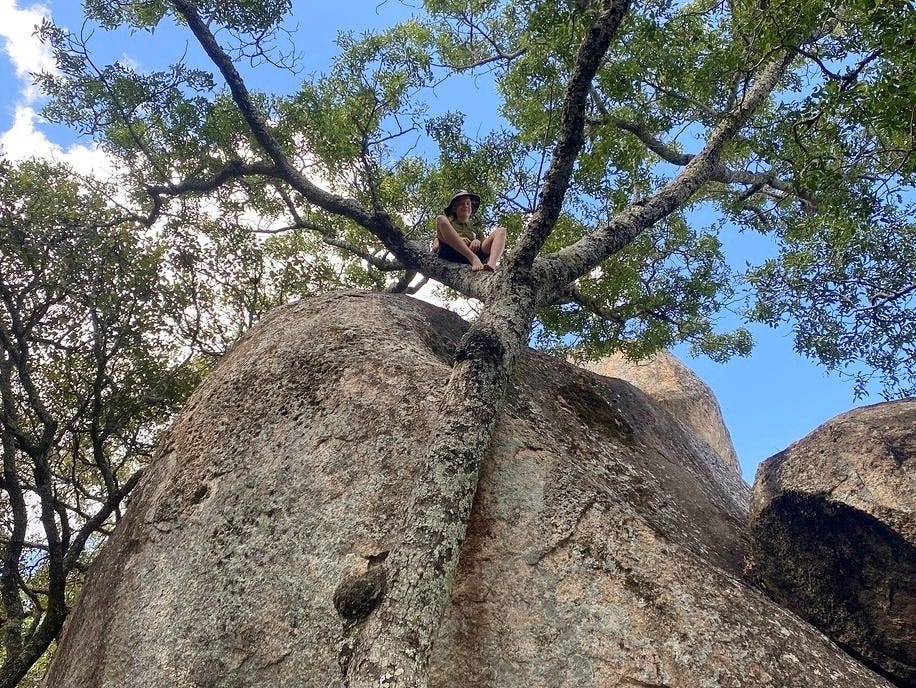

I watch my daughter clamber to the top of a giant rock in Harare’s Haka Park. The rock is overhung by Musasa trees. There’s something familiar about this playground…

A campsite just like this in the east of the country.

I was a little older than she is now. I'm with two friends on a hillock shaded by mountain acacias. My older brother cycles over from home. Evening is coming.

Already the surrounding woodlands are deep in shadow. Then, I hear it: a Black Cuckoo. It is a summer migrant from other parts of Africa further north.

Its plaintive three-note whistle is the sound of the dying day.

I whip out my notebook. “I just heard a Black Cuckoo,” I write to Dad. “It’s right near our camp.” I tear out the page and hand it to my brother. “Please give this to Dad. I want to tell him about a bird I just heard.”

He stuffs the note in his pocket, slaps his thighs, and stands up.

“Right," he says, "I’m off. Sure you guys don’t want to come home now?”

I glare at him and set about lighting the fire.