Stork-wing vests + Wild wax-eating guild + Africa’s rarest monkey + A happy discovery

Belief-based uses drive marabou storks near to extinction in West Africa

Marabou storks — among the largest storks in the world — are in trouble in West Africa. Researchers want them to be declared critically endangered across the region, according to this paper.

Their numbers have declined to as few as 100 breeding pairs. Since 2000, more than 60% of their breeding colonies have been lost.

In Nigeria the birds used to be common, and their breeding colonies were found near major northern towns. But the hunting of the birds by people for belief-based uses has seen all of the country’s breeding colonies wiped out. The last record of 8-11 breeding pairs of marabous in Nigeria’s Hadejia-Nguru wetland was in 1994.

The general decline in vulture populations across West Africa is thought to be fuelling the trade in marabou stork parts. Like vultures, marabou storks eat carrion. They are therefore perceived by some traditional healers to possess the same “powers” as vultures.

A separate study published last year revealed findings from wildlife markets in five states in northern Nigeria. Among the many marabou stork parts sold in the markets were a complete set of wings used as “a vest to protect the wearer against misfortune”.

Marabou stork. Pic credit: Ryan Truscott

New study turns up surprising number of wild animals feeding on beeswax

A new study has for the first time revealed the wide variety of animals that feed on beeswax – an energy-rich food source.

Until now, it was thought that few species other than the greater honeyguide bird were able to digest beeswax. Greater honeyguides famously lead human honey-hunters to wild bees’ nests. As a reward they’re often given beeswax by the hunters.

It’s a rare example of human-animal mutualism – an interaction from which both partners derive a benefit.

A team of researchers working in Mozambique’s northern Niassa Special Reserve set up camera traps at 26 sites where honey was harvested and beeswax left as a reward for greater honeyguides by Yao honey-hunters.

The team discovered that in addition to the honeyguides feeding on the wax, two other non-cooperating species of honeyguides came to get a share of the feast, as did honey badgers and African civets. But five other species not previously known to indulge also showed up: slender and Meller’s mongooses, African crowned hornbills, striped bush squirrels and yellow baboons.

A male greater honeyguide. Pic credit: Wilferd Duckitt, Wikimedia Commons

Information sought on Africa’s rarest monkey

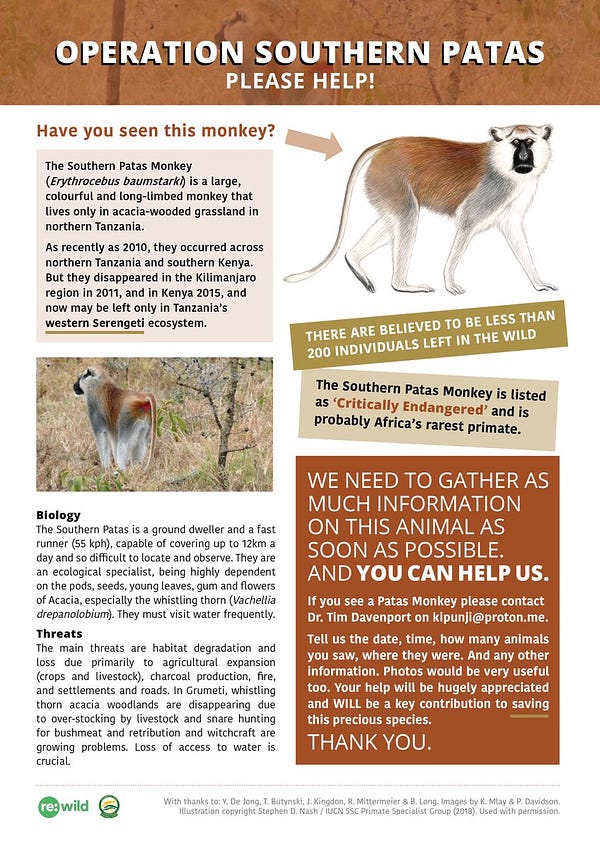

Conservationists need information on Africa’s rarest monkey: the southern patas monkey.

There are thought to be only 100-200 left in the wild. The species once ranged across 16.3 million acres (6.5 million hectares) of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. But they have, since 2015, disappeared from Kenya. Since 2011, they’ve also disappeared from the Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania.

A study last year estimated the monkeys’ extent of occurrence has now shrunk to just over half a million acres (200,000 hectares). Their last stronghold is in the western portion of Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park.

Tim Davenport, a Tanzanian-based conservationist, is appealing to tourists and tour guides to provide information on the date, location and number of monkeys seen.

The main threats to the monkeys, which have distinctive russet-coloured fur on their backs and long pale limbs, is hunting and habitat loss. The animals are dependent on acacia trees like the whistling thorn, and feed on its pods, leaves, flowers and resin.

A happy discovery

It’s a wonderful thing to discover paradise flycatchers nesting in your garden.

These small birds, with their fiery orange plumage, are intra-African migrants. In Zimbabwe’s cool dry winter months they migrate to lower, warmer altitudes in the south-east of the country or neighbouring Mozambique. In September, they announce their return with a torrent of cheerful notes.

Their songs become a constant refrain throughout the long summer months.

The males have long streaming tail feathers, and both males and females have vivid blue bills and wattles around their eyes.

Last week I was walking under the low branches of a Kei apple on my way to the washing line when a female paradise flycatcher flitted away. I looked up and there, on a spiny twig, sat the neatly-woven cup-shaped nest decorated with lichen and bound together with cobwebs.

I lifted our daughter onto my shoulders and she confirmed a clutch of three eggs.

“They’re a pale pink colour with purplish spots at the top,” she reported.

We quickly retreated and now we give the nest a wide berth to ensure we don’t disturb the parents, both of which incubate the eggs. I used a long lens to get this picture of the female sitting on the nest at the weekend.

Pic credit: Ryan Truscott